NL: Can you share your journey as an artist and how your cultural background has influenced your creative process?

WLC: I grew up in Houli, Taichung, in a family known for crafting saxophones. Our family has been making musical instruments for over 60 years. From as far back as I can remember, I would watch my grandfather’s generation crafting instruments in their old workshop along the streets. My father works in construction, and my mother is a fashion designer. The interaction with materials and the process of creating something from nothing have always been a natural part of my daily life.

During Japan’s 50-year colonisation of Taiwan, my grandfather’s generation was profoundly influenced by Japanese education and culture. As I observed their hands assembling and crafting brass instruments, engraving flowers and birds onto the instrument bodies, I also listened to their stories about Japanese mythology and their singing of Japanese folk songs.

I often visited my father’s construction sites, which were frequently located at the boundaries between the city and nature. There, I would see steel bars being tied together, concrete being mixed, and bricks being stacked into structures. Meanwhile, at my mother’s workbench, I would watch fabric being cut, sewn, and transformed into wearable, three-dimensional forms. These experiences embody the exchange and reception of culture. Using the materials around me to create something seems to have become an integral part of who I am.

NL: Your works often explore themes of nature and the human connection to the environment. How do you approach these themes in your art?

WLC: Solitude provides me with the spaciousness to amplify my senses and explore my relationship with nature and the city. I often revisit similar places repeatedly and continuously question myself to connect common elements, which become the foundation for some of my works.

Reading between the lines represents my exploration of the fluid zones between edges and lines, particularly the blurred boundaries between nature and culture. These boundaries are not as concrete as those on a map; rather, they are abstract, shaped by individual experiences and perceptions. Following the outlines of architectural volumes nestled in mountains, standing at the edge where mountain ridges meet the sky—these indefinable, shifting zones reside within every thought shaped by experience, and they captivate me.In my work, the use of empty space represents a neutral modulation of these fluid zones. It can be water, air, a boundary, or even a moment of stillness or speed. These spaces can serve as metaphors for anything imaginable.

NL: As a member of the Wilderness Art Collective, how has this community shaped or supported your artistic practice?

WLC: Before The Wilderness Art Collective became an organisation, we had already exhibited our works together at the Royal Geographical Society in London. We shared our observations and insights gained through direct engagement with nature. They enabled me to maintain an ongoing connection with London even after graduating from the University of the Arts London, allowing me to enjoy the pleasure of moving between different cultures and regions.

NL: Your use of different materials, including cloth, creates a unique texture and depth in your work. How do you choose your materials, and what draws you to specific ones?

WLC: The act of creating with my hands has been an instinct for as long as I can remember. The choice of materials is deeply tied to memories from my experiences.

Current stems from a cancelled journey, documenting an unfulfilled trip to Iceland in 2018. It reflects the inability to depart due to my father’s sudden illness and my yearning for Iceland’s coastline on the eve of the journey.

During that time, my mother’s resilience helped me face the fear of love and loss. Love and loss transformed into the entanglement of black sand and white waves along the coastline. The lines symbolising waves mirrored my mother’s hands, stitching together my nearly shattered perceptions. Textiles became something tangible I could hold, serving as a portal for tears traversing different dimensions.

NL: Could you elaborate on your series created with raw canvas? What inspired this choice, and what message do you aim to convey through these works?

WLC: The rawness and texture of materials are the first considerations in my creative process. Using raw canvas reflects the authenticity of the land, and I aspire for my works to be constructed with only the most essential elements.

As an artist who often works with water as a medium, the difference between paper and canvas in my experience lies in the speed of ink’s flow. On paper, ink can swiftly reach the direction I intend it to go, whereas on canvas, the flow is much slower, requiring more deliberate brushstrokes to advance it. These differences mirror the pace at which my consciousness drifts during the creative process.

NL: Your art often blurs the boundaries between traditional and contemporary techniques. How do you strike a balance between these approaches?

WLC: At the age of 10, I began practising the calligraphy of Ouyang Xun. Between the ages of 12 and 15, or perhaps even longer, I attended weekly art lessons at the Master Tsai’s studio near the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts in Taichung. My teacher, who had spent many years living in Japan and New Zealand, excelled in both Eastern and Western mediums and only returned to Taiwan to settle later in life.

During this period, I delved deeply into the works of Cézanne, Matisse, Monet, and Pissarro. Listening to my teacher’s stories from home and abroad, I naturally found myself filtering through the colours and structures of Eastern and Western art, selecting the elements I loved most.

NL: What role does sustainability play in your work, especially given the connection in your artworks with natural elements?

WLC: For those elements destined to be discarded during the creative process, I often imagine what they could be transformed into. For the final piece for my Masters at Chelsea College of the Arts, Invisible Cities, drew inspiration from Italo Calvino’s literary masterpiece, interpreting the concept of the number “three” and its multiples mentioned in the book through book sculptures. To this day, I still keep the pieces that were cut away. Me and the Leftovers involved reshaping leftover clay into new sculptures. These materials originate from the elements of the Earth, and after being fired, they possess the ability to eternally return to the cycle of nature.

NL: Can you walk us through your creative process when starting a new piece or series?

WLC: This has been a long journey. Reflecting on the works I’ve created over the past decade, I’ve come to deeply appreciate processes that unfold through the passage of time. The beginning of a new work often stems from connections formed through the accumulation of life experiences.

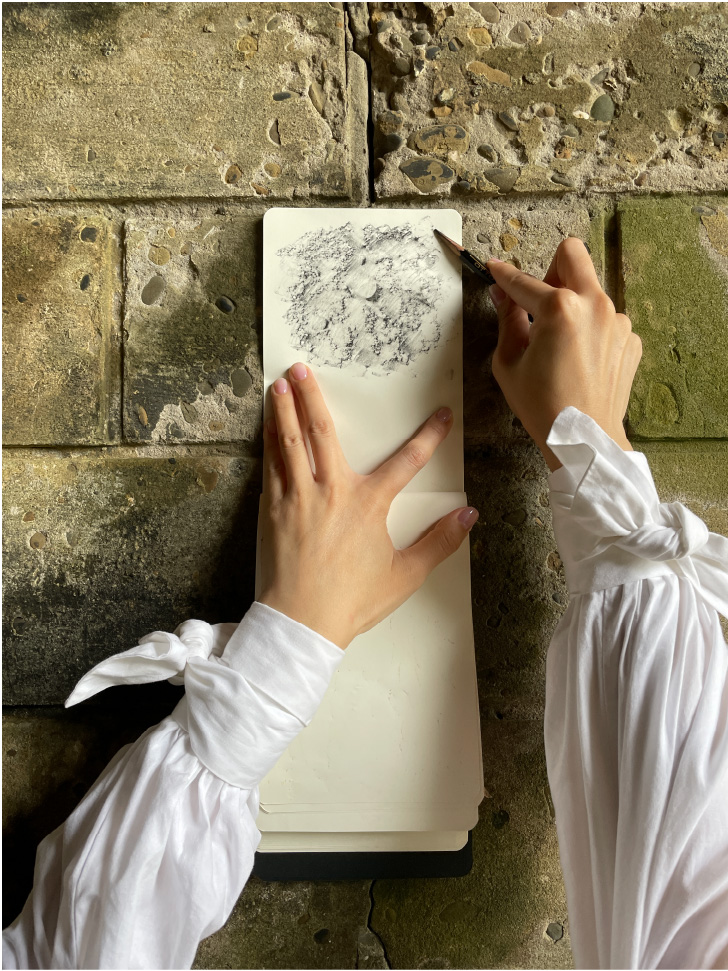

The Mediation series began with a series of unconscious gatherings—capturing the textures of nature through walking—and gradually expanded into imagery that dialogues with Eastern and Western art history. Unconscious collection, observation, and repetition are part of my daily life. These collections include words, emotions, images, and seemingly insignificant moments.

NL: Your works have been exhibited in various settings. How does the context of an exhibition space influence how you present your art?

WLC: The connection between my work and its environment, along with an emphasis on spaciousness, are my primary concerns. My largest steel sculpture stands on a narrow elliptical lawn in the middle of a concrete expanse, Still Mountain gazing across the Wu River towards the Jiujiufeng Mountain Range in Nantou.

This kind of subtle reading, one that invites careful or profound observation before revealing itself with a faint smile of cognition embodies how I wish to present art—hidden and understated.

NL: Do you have any upcoming projects or exhibitions that you’re particularly excited about?

WLC: Currently, I am collaborating with several artists on a walking project spanning Tainan in Taiwan and the Thames River in London. It is a series of interactions between Eastern and Western cultures, as well as contemporary influences, guided by Chinese pictographs. Another ongoing project, a self-portrait created using recycled clothing from close friends, explores the connections between individuals and their relationships.

NL: Do you offer art commissions?

WLC: I do. I also enjoy any form of challenge and collaboration. I have worked for five years with the I-Ching University in Taiwan on Lantern Festival projects. Still Mountain is one of them, where I developed a transition from the traditional use of bamboo or wood in lanterns to a more outdoor-appropriate metal structure. It was about finding a challenge between traditional art and contemporary practice that I could complete within the scope of the project. Over the five years, the expansion and possibilities of metal, how to plan its deconstruction, movement, and assembly, became the most necessary and interesting aspects to consider in exploring this work.

NL: Where can people buy your art?

WLC: The following websites and exhibition venues are where people can purchase my artwork.

The Wilderness Art Collective →

Wan Lin Chang Website →

Instagram →

Artist: Wan Lin Chang

Website: Wan Lin Chang Website

Exhibition: The Wilderness Art Collective

Instagram: @wan_lin_chang

Contact: artemischang@googlemail.com

Location: UK